as seen by a nomadic public service innovator in 2018

This report can also be downloaded as a PDF file.

The Lab

The Government Service Innovation Lab of Aotearoa New Zealand, hosted by the Department of Internal Affairs, is one of these “makers” pockets that found a way in government and bring within it an ability to do disruptive innovation.

These are not to be confused with other administration modernisation and innovation departments that focus on optimising internal processes. These more recent initiatives indeed leverage one specific way of modernising: they focus on the interactions between citizens and the administration. They aim at delivering high-grade, user-centred public digital services, in the open, within strong resources constraints. While counterintuitive at first, other countries have demonstrated the efficiency of this practice, and now recognise delivering services as the best strategy to improve agencies processes, driven by actual usage. The main similar initiatives around the world1 are gov.uk (UK, GDS2, 20113), 18F (US, GSA, 2014), beta.gouv.fr (France, DINSIC, 2015) and Team Digitale (Italy, AgiD, 2016).

Assets

Team

As for all of these other international examples, the primary asset of the Lab (if not its entirety) is a very motivated, talented, interdisciplinary and genuine team with a bold and visionary leader. The central role of such servant leaders is to empower their colleagues by acting as a “brick umbrella,” protecting them as much as possible from whatever the layers of bureaucracy above throw at them, allowing the positive and rewarding environment in which resilient and adaptable teams thrive. Such units leverage best engineering practices (continuous integration, continuous delivery, cloud hosting…) to ensure reliability and quality despite very constrained resources.

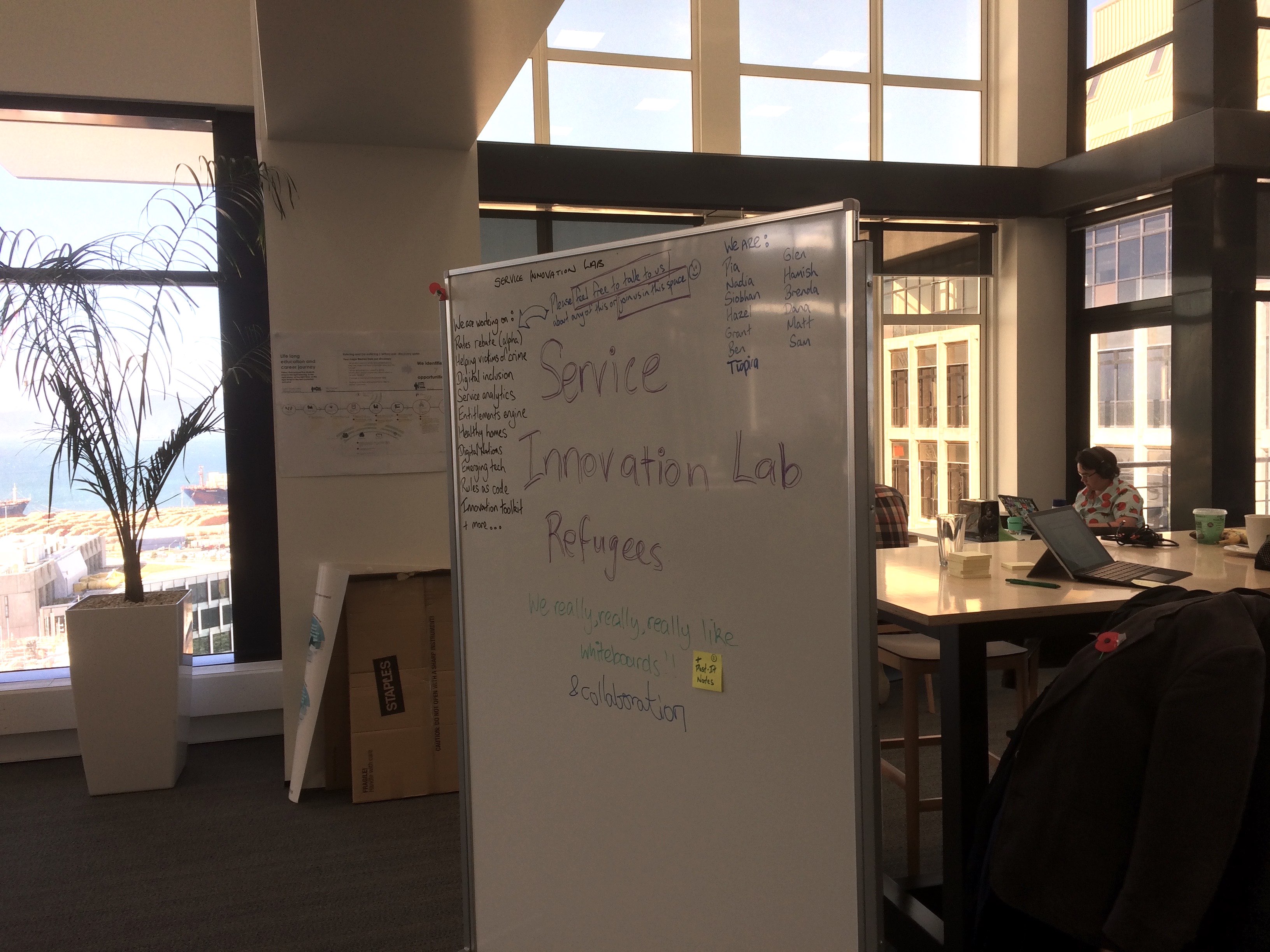

Lab meeting, DIA, Wellington, 2018

Lab meeting, DIA, Wellington, 2018

Capability

The Lab team has secured these elements for a few months and is now equipped with excellent delivery examples such as the Rates Rebate or SmartStart apps. These elements will build the mana of that team across and beyond agencies, giving it more ability to engage partners, in turn offering more delivery opportunities, in a self-reinforcing loop. The primary value proposition of Lab-like initiatives is an ability to deliver, thus demonstrating it is crucial to both growth and sustainability, and this one is well on its way.

Risks

Low leverage

Even while demonstrating its value, I believe that the Lab is currently too far away from central power to have a strong impact. All other successful examples I found, including all the ones cited earlier, are at most at tier 3 from Prime Minister or equivalent authority.

Innovation is about taking risk. By definition of bureaucracy, layers of hierarchy are there to mitigate risk. Even with the best umbrella, it is impossible to do visible, engaging disruptive innovation under mattresses. The first reason is that of the sheer amount of advocacy work that needs to be done by a team with already limited resources. The second is because a successfully delivered digital public service does not have the same inspirational impact on other agencies if it is “that DIA department” that did it or if it is “the GDS Ministerial Lab.” Status is an influential —and sometimes mandatory— element to diffuse innovation in a bureaucracy and engage non-cooperative actors.

Under-resourcing

The Lab will be unable to scale as such. It already operates over capacity, and funding uncertainty prevents investment. Since its team is made of people used to work within strong constraints, the risk is not so much of disrupting current operations or of limiting delivery ability; the actual risk is of burning out the team. Beyond the human impact, that would also mean a wasted investment: people who are competent in both their skills and government ways take a long time to grow.

It is worth noting, however, that it is a recurrent pattern for these very innovative teams to be at first ignored —or even mistreated— by their host agency until their value is impossible to deny. All of these now “famous” labs have their own horror stories of uncertainty and defensive struggles. I explain this by metrics mismatch: since they bring disruptive innovation abilities within government, the bureaucracy is not equipped to measure their effort and impact: there is no massive budget, no 100-pager to read in the cabinet, no 3-year outsourcing contract that are the usual signs of “big things.” Working software as the primary measure of progress, while indisputable for agile practitioners, is invisible for the administration until the value brought is too visible to deny that the problem is in measuring impact, not in having it.

The temporary Lab office after earthquake-prone offices had to be evacuated, DIA, Wellington, 2018

The temporary Lab office after earthquake-prone offices had to be evacuated, DIA, Wellington, 2018

I recommend focusing on delivery as the primary strategy, as funding will either be cut entirely at some point or finally recognised as the necessary fuel for a new way to deliver public digital services, and that second option can only happen by demonstrating how cost-effective that way can be by operating in the current constraints.

Scope creep

A recurrent temptation for makers who face administrative friction when changing one agency’s processes is to take up another challenge while waiting for the slower-paced political plays to unfold. Avoiding this is not possible nor desirable, as it is a sign of the entrepreneurial mindset that is precisely sought in such initiatives, and often yields unforeseen benefits4. However, the risk is to then expand the team’s responsibility to maintain or keep exploring too far, putting an even stronger strain on limited resources.

The current Lab scope seems too broad to be sustainable regarding both resources and organisational readability. Trying to be present at the same time in delivery, future tech (AR/VR) exploration, system-wide strategy, citizen engagement…, while useful to identify political boundaries and strengths considering its young age, will not scale.

Leaders that can engage makers must be visionary, which means that they sometimes can think too far ahead and overlook the burden of maintenance, prioritising investment over working budget. However, switching back to a managerial, accountant mindset is not the appropriate answer as it would very quickly disengage the team. I recommend to raise awareness of available resources, actual political engagements and associated funding streams, and to encourage and empower the team to take responsibility for their load from this information. Such a practice can limit scope creep while yielding the most innovation and fostering productivity.

Aotearoa New Zealand government innovation landscape

The Lab operates in a broader government innovation ecosystem. Beyond organisations, this section also takes an anthropological lens to characterise the inherent strengths and weaknesses of the cultural environment in which agencies operate.

Assets

The principal assets I have identified for Aotearoa New Zealand to innovate in government lie in its ability to go beyond silo mentality by sharing vision and resources both across executive-operational layers and across the public, private and community sectors.

Nimble government

Even though civil servants might not all feel action is fast enough, I have consistently observed a relatively short, 2 to 3 weeks time from first exposure to first action towards implementation of a new idea, practice or tool.

Delays of two months are common in continental France and can be even longer in overseas territories.

Frictionless operational communication

I have observed a distinctive kiwi positive communication style, with people genuinely reinforcing each other’s worth and value brought to a project. This could merely be a different way of expressing judgement5, but I attribute to this style an ability to engage on an operational level with less effort. With less risk of being shunned, agents from lower tiers feel more confident in joining a conversation. Similarly, Aotearoa New Zealand has the lowest professional gender bias of all countries I have observed. Since diverse operational insights are one of the basic needs for system innovation, this ability to engage is a definite asset.

Bigger bureaucracies tend to make it mandatory to inaugurate discussions through higher tiers, or even to prevent them until they establish a formal working group. Such a silo and layered mentality prevents serendipity and thus innovation.

“All-of-government”

All-of-government gives the conceptual, sourcing and partly practical basis for collaboration across agencies. Even with no extensive use of all-of-government contracts, the simple use of the term “all-of-government” as a shared notion makes it very simple for agents to state when they are willing to work beyond their agency’s boundaries and to quickly assess if their counterparts are as well.

In most countries, these practices have to be first established through peer-to-peer agreements, increasing the time to first meaningful collaboration.

Digital 7 operational relationships

The network of (self-proclaimed) “most advanced digital nations” D5, now expanded to D7, provides an excellent venue for sharing experience. Considering the natural duplicability of software and the commitment of these nations to work open-source, participation yields an extremely cost-effective way to reuse digital components and good practices. Sharing stories of successes and failures also brings new ideas and can prevent mistakes from being repeated.

Aotearoa New Zealand is culturally ideally positioned to benefit from such exchanges: it speaks the global English language, which ensures it masters communication and can access most information; yet it comes with a multicultural and multilingual understanding perspective thanks to its Maōri component, which helps it avoid falling into the trap of underestimating cultural relativity.

The USA in contrast, speaking only English, have access to as much information but have a tendency to dismiss other nations’ experience at the first sign of cultural mismatch rather than listening to the whole story and then extracting the pieces that make sense in their context.

Concerned network of private actors

With an understanding of the reputation of Aotearoa New Zealand as a clean, safe and socially conscious country as a shared asset, most private actors6 are more aligned with government objectives than in countries where the distribution of responsibilities simplistically opposes a right to regulate against a right to act until regulated. Community-conscious initiatives thrive and can quickly become partners of central and local government. As co-design is a crucial part of user-centred innovation and peer-to-peer diffusion an ingredient of adoption, this ease to work across legal entities is a strong asset.

Innovation agencies operating in countries where the administration is considered as corrupt or as an enemy spend a significant part of their resources compensating for reputation deficit when engaging with private actors and individuals.

Quest for clarity

All stakeholders of an action, be it standard service delivery or significant process change, seem to look for a clear understanding of why they are engaging in an activity. Artefacts (posters, flyers…) stating and reinforcing end goal visions are omnipresent, and ceremonies (team meetings…) are used to that effect as well. Since radical innovation, by profoundly changing processes, can only pay off with alignment across layers, the familiar presence of tools and practices for diffusing vision is a definite asset.

In countries that take a top-down approach to action, operational agents training to follow a process rather than being engaged in it hinder change initiatives.

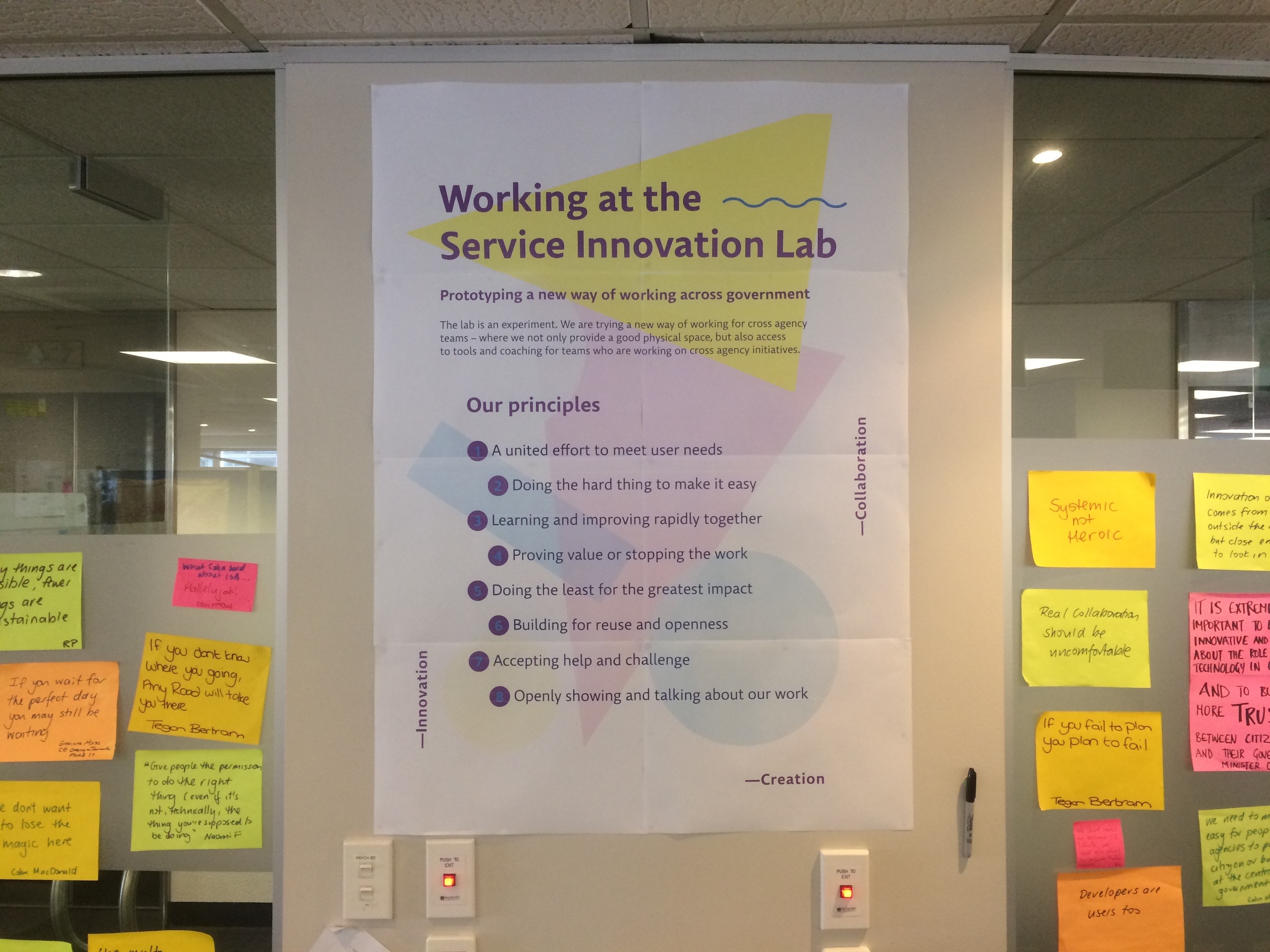

The Lab front door, Wellington, 2018

The Lab front door, Wellington, 2018

Risks

The main risks I have identified that can hinder government innovation lie in missing the tools to challenge the status quo.

Consensus over action

Innovation is all about questioning ingrained habits and processes, and while its construction should be collaborative, its impact will by definition change the way stakeholders work. The flip side of positive communication is that it can be hard to distinguish clearly between enthusiasm to participate and actual commitment or to go through productive conflicts, which can then limit the ability to act on known problems. Waiting for all actors to be fully aligned with a vision prevents experimentation from happening, while the result of said experimentation would often be the most effective demonstration. Any strategy is only worth as much as the ability to deliver upon it.

In the UK, the strategy was very clearly stated: “digital by default” and “assisted digital” make for such strong directions that they are now the Digital Service Standard. But only by following “the strategy is delivery” could these have any actual impact.

Funding instruments and ambition mismatch

If the ambition for innovation in government is to have public digital services delivered in an agile, user-centred and experimentation-based fashion, then competitive funding is counter-productive. Innovative products are best produced within short timeframes by small teams of people who typically don’t have a lot of capacity or interest for long descriptions and plans —which is why they are the best fit for “de-bureaucratising” processes on behalf of end users in the first place. This fact implies that public innovation is best funded by small grants given to agencies with concrete use cases and strong teams. To ensure doing gets an advantage over planning, application to these funds should have an aggressive, unusual format that aligns with the expected result.

In the USA, 18F engages very early, by email, and expects the problem to be defined collaboratively. In France, the State Startups Incubator only works with agencies that have identified a civil servant intrapreneur providing a one-page product description7.

Underrating of public digital infrastructure

Offering capability to the economic and community components of society does not mean having an empty government. On the contrary, stable infrastructure yields more benefits to all. If Aotearoa New Zealand is to position itself as an “information society,” it is critical that it recognises the need for the digital infrastructure that will enable this. Just like sewage and roads are critical water and transport systems that allow healthy communities and strong economic actors, a knowledge-work society needs strong, maintained and up-to-date pipes and hygiene.

This starts by ensuring agencies consider software as an asset, not a liability. And continues by providing a robust and secure network of connectivity and hosting providers, which can be public or private, but that should all be within New Zealand sovereignty area. This notion of public digital infrastructure should also extend to data.

France has for example pioneered the notion of “public data service,” identifying nine datasets as being critical for agencies and companies alike, and enshrining their availability and quality in legislation.

A long-standing piece of infrastructure: the railway station, Wellington, 2018

A long-standing piece of infrastructure: the railway station, Wellington, 2018

ICT strategy recommendations

This set of recommendations builds upon the previous observations, as well as on my reading of strategy documents, participation in an ICT strategy co-design session, and interviews with participants before and after it. It aims at complementing and influencing the current directions, not replacing them.

Focus on capability

An important area of focus for the current ICT strategy is rephrasing elements that were already discussed under the previous government. While political alignment is a manifest necessity for public action, a strategy that aims at enabling delivery and transformation should affirm focus on impact and capability mapping to embody the priority given to investment and action.

The time for government as a platform is now

Actually, it was yesterday. Platform economics are already ruling the world of knowledge work. New relationships have to be built between government, economy, and society. Every day that passes where the government keeps policing through only regulation and strategies rather than building enabling platforms is more power flowing away to the GAFAMs and a lost opportunity to the people of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Parliament House with national flags, Wellington, 2018

Parliament House with national flags, Wellington, 2018

Such platforms should provide agencies, companies and individuals alike with APIs to interact with public services, interconnecting society components and providing governments with soft yet immediate and measurable power by regulating these platforms.

Fund public innovation

Create innovation funding instruments that allow other agencies to replicate the Lab’s achievements: small grants, small descriptions, small durations, big ambitions. And then shine the spotlight on these other agencies’ realisations.

Larger-scale transformation funding would then be most effectively provided to agencies that have already demonstrated an ability to deliver smaller-scale services. Without implying that the exact same practices can be applied on any problem, there is a definite risk limitation in knowing that agents have first-hand experience with lightweight methods and fast delivery when tasked with updating large systems and processes.

The Lab is one piece of the puzzle

Use it to spearhead, demonstrate, engage, hire. The Lab will never deliver all public digital services, nor should it aim to. But it can be used to show what all agencies should try to emulate. Make it grow and evolve similar initiatives across central and local government, by getting Lab alumni to mentor them. Use the Lab reputation and skills to hire highly skilled digital professionals, and trust the Lab to facilitate their onboarding: it is the only part of government that speaks their language.

Better Rules hackathon final presentations, Wellington, 2018

Better Rules hackathon final presentations, Wellington, 2018

This document is licensed under Creative Commons Non-derivatives 4.0. You are free to redistribute and share it as long as you attribute it to “Matti Schneider for the New Zealand Government’s Service Innovation Team” and do not alter its contents.

-

I do not include state-wide digital initiatives in countries such as Estonia or Singapore. Indeed, while yielding a very capable digital government, these do not face the same challenges of transforming an existing massive system, and thus have very different adoption and political strategies. ↩

-

Expanded acronyms of host agencies are: Government Digital Service for gov.uk, General Services Administration for 18F, Inter-ministerial Direction of Digital and IT Systems for beta.gouv.fr, and Agency for Digital Italy for Team Digitale. ↩

-

Dates are official opening years. In most cases, under-the-radar pilot cases had taken place in the preceding months. ↩

-

The French api.gouv.fr portal, the Agencies Directory API and verif.site all started as small prototypes made under 2 days by “bored” yet empowered members of beta.gouv.fr. This also illustrates why innovation needs operational engagement. ↩

-

For example, by giving negative feedback through the absence of positive feedback. ↩

-

“Private actors” as opposed to public actors, not considering whether they are for profit or not. ↩

-

All these descriptions are publicly available. See for example the one for Now!, a State Startup from the unemployment agency. ↩