Rates Rebate Beta - Research Report

The research was conducted throughout the Beta project from February to June 2019. The research was a combination of customer interviews, council and stakeholder observations and conversations, online surveys and analytics analysis.

Content

Key insights

- The system is too complex and multiple errors are occuring

- Seniors are more digitally capable than many assume

- Applicants are relinquishing control over to the council and authorities

- The current process is not accessible to people with disabilities

- Retirement village residents were well supported and have wrap around services

- There is a significant appetite for various forms of automation

- Eligible applicants are not applying because their personal data is not private

- The statutory declaration is a significant barrier to the completion of the process

- There is a need for human contact and support

- Newly bereaved need additional help with the application process

- Leverage the best channels for awareness and support

Appendix

Executive Summary

The Rates Rebate scheme provides a rebate of rates to eligible ratepayers to assist low-income households. The process is administered by local councils, who are then refunded by central government. The final amount of rebate available to an applicant is calculated by their household income, their total rates bill, and the number of dependants in the household.

The Service Innovation Lab were commissioned to work on this initiative and completed a Discovery and Alpha phase. It was identified during the Alpha phase that deeper research and engagement was required to understand the barriers to completion, and how to improve uptake of the entitlement. This research informed the recent Beta phase of the project.

The design research was a combination of surveys, analytics and face to face interviews with the applicants and council staff. The research has informed ways to improve the access to the application, and to remove barriers to completion. We have been able to use the results of this research to restructure the online content on govt.nz. We have also been able to advise the DIA Service Delivery and Operations team on how improvements can be made to the existing paper application form to increase legibility, comprehension and accessibility.

We’ve identified areas of improvements that can be made to the design of the end to end service to reduce errors, to improve accuracy, accessibility, privacy and efficiency of processing. These improvements will reduce cost and burden on the applicants, council and DIA teams. This also helps move towards delivering on the intent of the Rates Rebate Act. The biggest identified barrier to completion remains the requirement of the Statutory Declaration.

“The elderly are very susceptible to winter illnesses, and yet they often come out of their sick beds and warm houses to sign.” COUNCIL STAFF MEMBER

The research has helped us understand this audience segment and their trust and perception of government and local council. It has also challenged our initial assumptions about the digital capability of this segment, and have proven that this group are more digitally savvy than perhaps expected by many. They also have a high expectation of interacting online. This research has also informed us on how to better engage with this group with style of language, content structure, and the channels and communities in which to reach them.

We’ve identified the friction with processing retirement village applications through the councils, and the current work arounds, and foresee a reduction in uptake across retirement villages in the next rating year. This is something that can be integrated and improved with future iterations of Rates Rebate online.

Background

What is Rates Rebate

The Rates Rebate scheme provides a rebate of rates to eligible ratepayers to assist low-income households. The process is administered by local councils, who are then refunded by central government. Applicants need to apply every year by providing an application form and proof of income to their local council.

The maximum rebate available is currently set at $640. The final amount of rebate available to an applicant is calculated by their household income, their total rates bill, and the number of dependants in the household.

Who applies for a Rates Rebate

Most recipients of a Rates Rebate are superannuitants. In the 2017/18 rating year 79% of all successful applicants were receiving New Zealand Superannuation. Other recipients were 14% employed, 4% on other benefits and 2% unemployed.

In February 2018 the Rates Rebate Amendment Act 2018 was passed. This amendment grants those who live in retirement villages eligibility to receive rates rebates (in the form of a refund). As a result of this change, uptake is expected to increase in coming years.

The total number of ratepayers eligible for a rates rebate is not known.

What work has been done by the Lab for Rates Rebate

The Lab produced and tested an Alpha prototype with Tauranga City Council between May and September 2018. The Alpha proved to be of high value to ratepayers and Councils, and successfully tested a fully digital and user centred end to end rates rebate process. It was identified during this Alpha phase that deeper research and engagement was required to understand the barriers to completion, and how to improve uptake of the entitlement. This would help the team understand the nuances of this group and to understand the cultural attitudes around receiving money or help from institutions.

The Beta phase focused on further refining the service based on further user research and feedback from ratepayers and three councils. This report is a summary of the research findings with applicants and council staff.

Methods

Research Questions

The two primary areas being explored with the Rates Rebate beta were; could a solution like this increase uptake of the Rates Rebate, and could it improve customer experience and satisfaction levels (also the Outputs section for more). In order to inform solution design, both for the beta phase and beyond, we determined we needed answers to the following questions.

- What is the current state of awareness?

- What are the best channels for awareness and completion?

- What is the digital capability of this cohort?

- What is confusing?

- What creates blocks to completion?

- What are the costs (including time, money, cognitive load, dignity)?

A variety of research methods were used to get the information we needed.

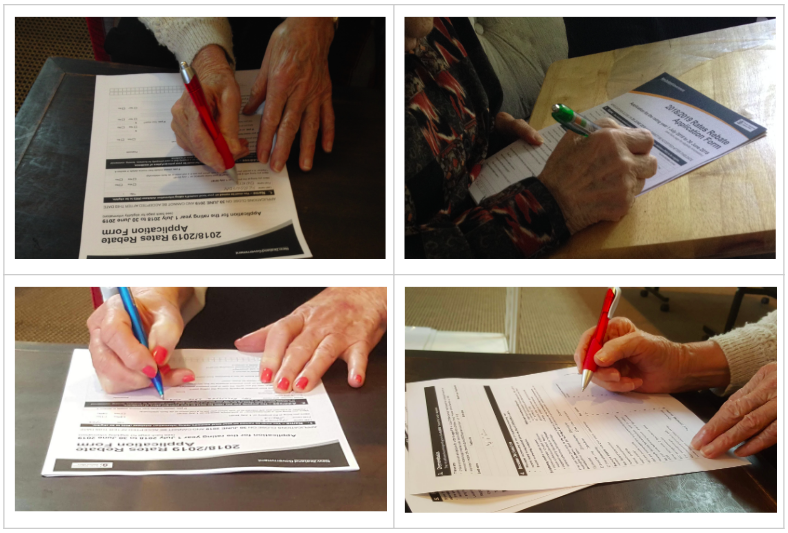

1. Interviews with applicants

In April 2019 we conducted interviews with nine eligible Tauranga ratepayers, over five days. Tauranga City Council helped us identify people we could interview that covered both the majority of eligible customers, and edge cases. The interviewees were recruited by Tauranga City Council, based on residents who had previously applied for a Rates Rebate, and therefore were a fair representation of those eligible and apply for a rates rebate.

Eight of the interviewees were over 65 and receiving superannuation. One interviewee was receiving an alternative benefit. The interviewees were a mix of people who lived in retirement villages and their own homes. They included people with English as a second language, and people with reduced mobility.

The semi-structured interviews ran for 1.5 hours, and were conducted in people’s homes, retirement village rooms, and the local library. The interview process was a mix of visual cards to prompt dialog on current and future states, card sorting to reveal degrees of difficulty in the process, and potential supporting channels, filling in the existing paper application to identify what is confusing and a barrier to completion. Interviews were recorded by dictaphone, and photos taken of relevant steps. The recordings have been transcribed for analysis.

2. Conversations with council staff & Department Internal Affairs

Conversations were conducted with Tauranga City Council, Hutt City Council, and Kāpiti District Council throughout the Beta phase. We observed the processing of applications at each council, and the unique system each council used. Additional conversations were held with Wairarapa councils to understand their process and pain points.

We worked alongside subject matter experts from Rates Rebates team, within the Service Delivery and Operations branch at DIA.

3. Online surveys

Survey research targeted existing visitors to the Rates Rebates section of govt.nz. Two surveys ran during the Beta project. The initial survey ran for two weeks at the start of the project, before any changes had been made to the content. A follow up survey ran for three weeks during the Beta trial to gauge visitors perception of the process and the changes implemented on the online application form.

4. Analytics analysis

We identified a set of data that we could pull from analytics on the original Rates Rebates section of govt.nz. This helped us understand current baseline behaviour, search patterns and plan appropriate content structure. The process and the results of this are available as a blog: ‘Rates Rebate - content changes lead to better experience, more users’

Outputs

Synthesis

Once we had gathered all the data, we went through multiple steps of analysis and outputs. Because this activity was conducted in parallel with the Beta build, we were only able to implement improvements based on early insights immediately into the design of the service. Additional insights have surfaced as we have put the Beta online trial into production. It is hoped these can drive further improvements beyond Beta.

The results from this research inform how we might

- Help increase the uptake of the Rates Rebate

- Improve customer experience and satisfaction levels

- Decrease the cost of processing applications for councils

- Improve the ability to digitally deliver this and other services to councils

- Support the case to remove the statutory declaration (witnessed signature) requirement

- Reuse these insights for other use cases that have similar customer profiles

This report was produced in parallel with the Rates Rebates Beta Recommendations Report which documents the key results of the trial, presents options for next steps, and makes a set of recommendations.

Key insight #1

The system is too complex and multiple errors are occuring.

Ratepayers find the current paper application form confusing. This leads to forms often being completed incorrectly, or required fields left blank. Applicants often perceive the ‘rates’ and ‘income’ step as easy, yet will frequently get this information wrong. Councils suspect there are a large number of ratepayers not applying because the process is so daunting.

The rates amount required is a combination of local, regional and water rates which differ across regions. Applicants rarely have this information at hand, and can misinterpret what is needed. Councils have requested the rates field to be removed completely from the application form, as staff were continually correcting this data. Occasionally the information will be corrected after the statutory declaration has been signed. Retirement village residents don’t know how much they pay in rates, and rely on the village administrators to provide additional information to allow them to complete the application process.

The income amount required is the total income from the previous year, before tax. Applicants often enter their income based on what appears in their bank account, then do a rough calculation to add it up to a year. This results in an inaccurate amount. Income amounts for benefits change depending on the year and individual circumstances, and very few people know the exact amount. DIA have supplied an income guide to councils to assist in helping applicants fill in the amounts. Having a list of possible incomes was helpful as a checklist prompt for applicants, but some didn’t know which benefit category they were in. Some didn’t bother to declare interest on investments because they considered the amounts too small to be relevant.

“I’m thinking, surely you want to know what I actually get, not what was there before tax”

“Proof of income - that was blimmin hard”

The definition of Dependants was commonly misunderstood by both applicants and council staff. This meant that applicants may miss claiming for a dependant family member who live in their household. This can impact their eligibility for a rebate. Details about a dependant are not legally required by the Act, and asking for this data may add a barrier to completion.

Multiple dates in the application are difficult to understand and remember. A lot of people enter information for the wrong year. Some applicants mistakenly apply more than once a year.

Key insight #2

Seniors are more digitally capable than many assume.

Superannuitants are using websites and apps to achieve a wide range of tasks. There is high use of PCs, laptops, tablets and mobile phones in this demographic. Interaction online allows the applicants to apply in their own time and at their own pace. The barrier identified is access to the hardware and internet services rather than the ability to use digital systems.

Three quarters of the superannuitants interviewed are interacting online and are digitally savvy. Facebook, Skype and emails are commonly used to connect friends and family. A large proportion use these applications for video calling, sharing photos, and sending messages.

Google is used for searching and map locations. Appointments, sports games and holiday accommodation were booked online. Tracking apps were used to measure fitness and performance in walking and golf. Purchases were made through Trademe and Amazon. Ancestry was also used to explore and track genealogy. Various surveys, competitions and special offers were completed online.

“Google is amazing what you can find” “It needs to be simple”

“The iPad is just part of me - it sits next to me in the arm chair”

“Even oldies have got their phone - what would you do without it?”

Online banking is popular, but this demographic were also very wary of sharing their bank details online due to a lot of publicity about scamming. Retirement village residents have no problem writing their bank account details on the paper declaration form for the application process. This is because there is a high level of trust that authorities will keep their information safe. Further testing will be needed to investigate comfort levels if bank account details are required for the online process, when village residents are applying for a refund.

Financial constraints were stated as a barrier to either replacing technology that had stopped working, or buying a new mobile phone or tablet. The main requirements of using digital devices and systems is that it needs to be easy, and the users need to be in control.

Key insight #3

Applicants are passing over control of their application to council and authorities.

Councils inform us that applicants often leave required fields or entire application form empty, and trust that council staff will enter or edit details correctly on their behalf. Although the applicants are signing the statutory declaration, they are doing so because they have a high level of trust in the decisions made by their local council staff.

The application process is often seen as being complicated, so applicants often allow council to guide them through the application, and make suggested inputs and changes. There is a lack of clarity around the role council staff have in authenticating the proof of income. This can mean that the responsibility of verification frequently falls to the council staff member, rather than the ownership of the declaration staying with the applicant. There are some applicants who will leave a large folder with documentation, expecting the council to check complex account details.

We have heard from these customers that they need financial security, freedom, and to be in control of decision making. They like to track what has been done and when, and keep a paper trail of the process. This contrasts with the ease in which they are handing control over to other entities and authorities.

“It’s just government stuff. I’m not bothered. I’m past it now, you know, caring”

They don’t question those perceived as authorities. They have a high level of trust in local council and government, trust in the retirement village operators, and trust advice given by their accountants and lawyers. There is a lack of need to understand the complexity of the process, and a level of comfort in passing the decisions over to other authorities.

“A lot of it was done for us. It just made it really really easy”

Retirement village residents relied on the village administrators to provide the additional supplementary form information. There were some applications that were stalled at council, unable to be processed, because the retirement village administrators had not provided the additional paperwork. There is no guarantee that these forms will be supplied to allow the application to be processed, and the applicants to receive their reimbursement.

Key insight #4

The current process is not accessible to people with disabilities.

With approximately 11% of the target audience vision impaired, 49% with a physical disability, and 59% with a disability of some kind, there is a high need for the process to be fully accessible.

The applicants interviewed all used reading glasses and struggled to read the smaller text on the paper application form. If the application form is accessed as a downloadable pdf, it’s possible to enlarge the text, but the content doesn’t reflow into the screen, therefore comprehension is compromised. The downloadable pdf hasn’t been tagged with appropriate markup labels, therefore is not accessible to those using screen reader technology.

“I’m partially blind, so if things are on a computer I can zoom in and read them”

The process of Rates Rebate is complex and the wording confusing, and full of government jargon which places cognitive load onto the applicant. There are multiple dates to remember, and applicants struggle to remember the details of previous applications. A proportion of the interviewed applicants had impaired hearing, and can struggle to comprehend the details of the process when speaking to someone on the phone.

Dexterity is impacted and a large proportion of applicants have difficulty writing their details on the form, and the process of signing their signature can be challenging and demeaning. The paper form requires the applicant to repeat a lot of the same information.

“Sorry, my fingers don’t work very well”

The requirement to physically present to council to sign the declaration can be impossible for people with mobility challenges without getting help from others. This is acknowledged as the most significant barrier to completion. At busy times in the rating year, the applicant will need to stand in a queue while waiting to have their application processed.

“Trouble is I can’t walk very far now. My knees and my ankles have packed up. I can’t drive at the moment because my shoulder’s packed”

Key insight #5

Retirement village residents were well supported and had wrap around services.

In February 2018 an amendment was made to the Rates Rebate Act to grant those who live in retirement villages eligible to receive rates rebates (in the form of a refund). This first eligible rating year has been supported by local councils, with a concerted effort to reach retirement villages in their region to give support, information and additional service.

Local councils have provided reach and information to residents through the support network of each village. The council staff visited retirement villages to help support and process the application, and provide the necessary additional forms. The applicants had the application forms brought to them, the supplementary rating declaration provided through the village, and the council visiting to help with enquires and witnessing signatures. This removed the need for applicants to visit their council to sign the statutory declaration.

As a result the experience of village residents has been very positive, and for most, the first time applying for a rates rebate reimbursement. There were some examples of information getting misconstrued between villages, local council and the residents, but the applicants generally found the process straightforward and easy.

“For living in the village, it’s just really easy, we don’t have to remember because they come to us”

“They were very helpful, the lady that was here”

However, the rates paid by residents are not transparent or readily available, and applicants rely on the village administrators to supply this information to them, and to provide the authorised signatures on the supplementary information form. If the village administrators do not supply this information, then the application form cannot be processed. There were examples of applications waiting at council offices, that could not be processed because the supporting documentation from the village administrators had not been completed.

Further research is recommended to observe the next rating year and the uptake from this segment as the local councils will not be providing the same level of promotion or visits to the villages.

Key insight #6

There is a significant appetite for automation.

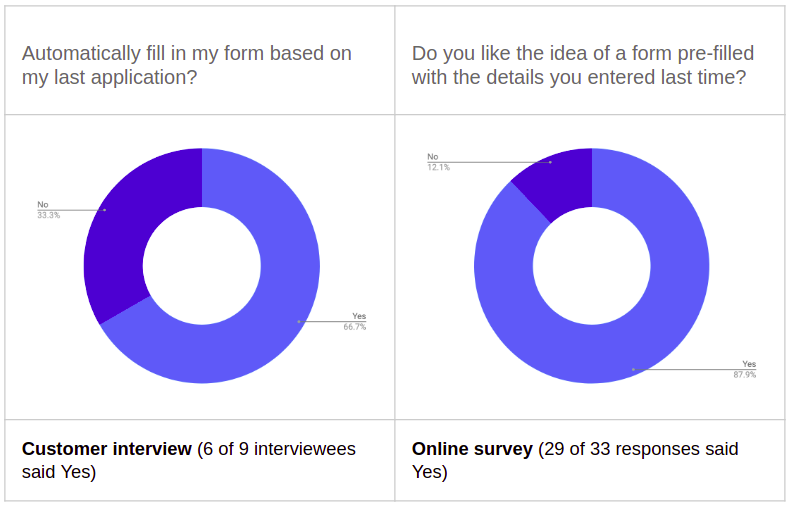

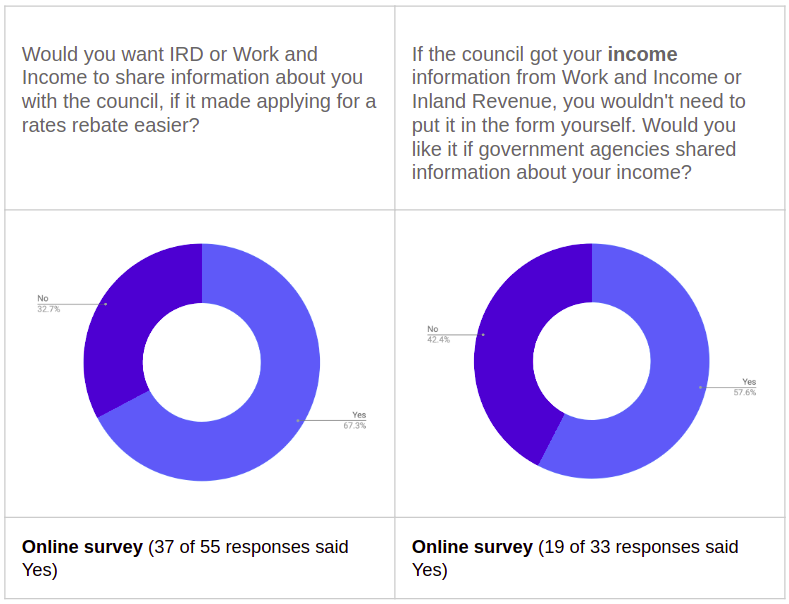

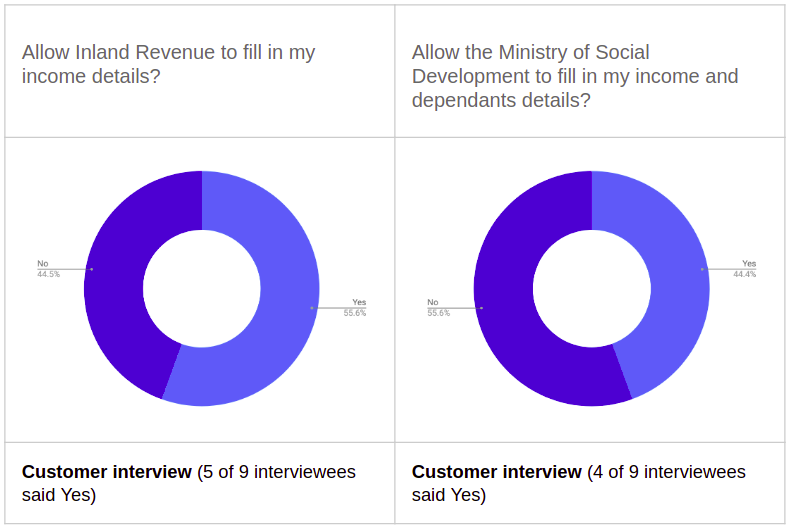

Results from surveys and interviews indicate that the majority of applicants would prefer to have the form prefilled based on their previous application. There was a significant appetite for allowing government departments to share their data and assumed this is already happening.

Eligible ratepayers are surprised that they are required to fill in the form manually every year. This perplexes a lot of people as they find repeating the process of getting the information from separate government authorities inefficient and a waste of time. People’s circumstances don’t generally change each year, yet the same information is required every rating year.

While some people kept documents in a folder for easy reference, other applicants lost documentation altogether. This meant that applicants would need to contact Work and Income, Inland Revenue and banking institutions to get documentation for proof of income. There were instances of applicants receiving the wrong information or advice at this step, and either giving up or missing the application date altogether.

Dates are difficult to understand and people struggle to remember how they did the process previously. Applicants frequently reapply within the same rating year, not realising they have already applied, and turn up unnecessarily to the council. Some applicants don’t remember to apply from year to year and need to be reminded by their council.

Applicants will often identify as names other than what appears on the Rating Information Database, such as middle or shortened names. This can cause slow downs at council when the application is being processed. Current process with paper application requires double handling and repetition of data entry.

“What a huge waste of low-income earners time, when we could be working to earn more money.” ONLINE SURVEY

“I think all low-income households who have a current community services card entitlement should be able to apply without so much fuss. I currently have to fill in forms, sit and wait at a JP office and then post or physically drop all this into the council.” ONLINE SURVEY

Key insight #7

Eligible applicants are not applying because their personal data is not private.

There is some embarrassment about income and asking for any form of help which was a barrier to applying, especially in smaller communities where the applicants are likely to personally know the council staff.

There are important cultural attitudes around receiving money and help, and during the research we found evidence of some, but believe there is more. There is currently no visibility of the people who are eligible but choose not to apply for this reason, so further research could be explored in this area.

Because there is a legal requirement for the signatures on the statutory declaration, most applicants visit council offices to process the signatures and risk having their details discussed in a public space. Additional data is gathered but not required in the legislation, and lack of clarity of process has led to inconsistent outcomes. The process is open to an individual’s interpretation of the rules, personal decisions and unconscious bias.

During the three week Beta online trial there was an enquiry from a potential applicant who wanted to know if the council staff would be able to see their personal information. When discovering that their information would be visible to council staff, they declined to apply.

“Anyway, being a much smaller town, more often than not we know those bringing the forms in” COUNCIL STAFF MEMBER

“Whilst being appreciative some of them are also embarrassed to have to come in and feel like their financial situation is scrutinised.” COUNCIL STAFF MEMBER

“Some people may know about it but not many would share this information with each other because they don’t want to share their income or let people know they are on a low income” APPLICANT

Key insight #8

The statutory declaration is a significant barrier to the completion of the process.

The current statutory declaration requires the applicant to be physically present at the council office or other stated authority to sign and witness their application. This adds financial cost of travel, stress for those with declining mobility or those who are embarrassed to apply for a benefit style payment in a smaller community.

Older customers are more likely to have age onset disabilities that make it difficult for them to get out and about to be able to sign for the Rates Rebate. For those able to drive, finding parking close to council offices can be challenging, as can getting to the council during business hours. There are applicants who are unable to drive and rely on others, or incur the cost of a taxi. Some applicants need a support person with them, and need help with interpreting and understanding the process. Some are unable to walk or stand for long periods of time, housebound or hospitalised. Some applicants are the caregiver for their partner, and they need to arrange additional care for their partner, while they visit the council to sign the form.

Some applicants have mental health issues and can only come into Council on a ‘good day’. The good days can take some work, and add to the overall stress for applicants. Some can react and become volatile, and can put the council staff at risk. Some applicants can have high anxiety and can be too scared to leave the house.

Council staff often visit applicants at home to allow them to complete the process. Home visits need to accommodate for staff safety, so it takes two staff members out of the council team, and takes out the use of a council vehicle. Councils will often employ extra staff to cover this busy time, but for some councils it’s not practical to do home visits because of the spread over remote outlying areas and small staff numbers. There has been added confusion and rework with the wrong people witnessing (e.g. Real estate agents, family or non CA accountants).

“The On-line process is very straightforward, however the requirement to make a declaration in front of a council officer somewhat defeats the on-line process.” ONLINE SURVEY

Statutory declaration: Council stories

“She got a taxi to drop her to our offices, she got halfway through the doors and needed a chair to rest to catch her breath and rest her legs. Then she made it inside to the counter and sat down while I went through her rebate with her. Then I had to escort her to our cashiers (stopping midway to sit and rest) so she could get some cash out and order her taxi home. It was a big ordeal for her which had her in tears.”

“He has a head injury and is very volatile. It depends on the day as to what response you will get when you do a home visit. It takes two staff members to visit him and sometimes he won’t let them in!”

“She is bed bound, not just housebound - so the staff have to go in to her bedroom every year. She has to arrange for her home helper to be there when the staff come so it takes a bit of arranging for her and I am sure it is quite intrusive having administration staff from her local Council in her bedroom.”

“She is housebound and asks family members who need to coordinate the visit so they can be at the house and explain things to the ratepayer and just be there for reassurance. Often the ratepayer doesn’t really understand what is going on and the disruption to their normal routine and having strangers in their home is very upsetting.”

“He is schizophrenic and doesn’t like people so won’t come into the Council building. Staff phone his caregiver and arrange a time and she drives him to the car park and staff go out and witness his signature in the car park.”

“She has 6 young with children with medical conditions. It is extremely difficult for her to organise the time to come into the Council to have her application witnessed.”

“The elderly are very susceptible to winter illnesses, and yet they often come out of their sick beds and warm houses to sign.”

Key insight #9

There is a need for human contact and support.

There is a need for the applicants to be able to talk to someone for help, even if the system is automated. Most applicants are comfortable using the phone to make an enquiry, and will use often talk to someone to understand how to navigate the system.

Customers often call Council or Citizens Advice Bureau to ask ‘How do I start?’. They want to talk to someone to understand clearly and easily what they need to do. People who are really marginalised and needing help often just need to talk to someone in person.

A complex system can be better delivered as an automated process, however automation can also bring gaps and oversights in the system. This can lead to individuals dropping out of the system. Our research surfaced an example of an individual who missed getting a Community Service Card because of an error made through the IRD system miscalculating income. This meant eligibility for other services and support was denied.

While the bulk of Rates Rebate applications can be processed with an automated approach, there is still a need for the system to build in human effort for the edge cases or enquiries. The skills of the service centres can adequately provide customers with the support they need. In this way the process can prioritise meaningful human interactions.

One of the council service centres is in the process of installing kiosks to support those customers wishing to self serve a transaction. A concierge service directs people to the service they require, and can answer their questions. If they are there for an enquiry they can go talk to one of the staff. If they really want a human to do their transaction for them that’s ok too, they may just need to stand in a queue.

The majority of the group have heard about Rates Rebate from friends and family, or through their local council. Applicants often get help from their family, support networks or from council staff to help fill in the form. There are some applicants who enjoy the interaction with the council, and will make an occasion of it, dress up and make a day of it. They enjoy the process if it is a positive one, but get very frustrated if they get the wrong information or need to wait.

“Talking to someone about it - so that made me happy”

Key insight #10

Recently bereaved need additional help with the application process.

Recently bereaved applicants struggle to cope with taking over the household administration if they have not done it previously. Some applicants can find the process daunting and overwhelming in addition to the other tasks left to them to manage.

A common scenario is that the applicant has had to care and support their unwell partner, and then is left to cope with the burden of taking over all the household administration tasks. This is also impacted by the grief and upheaval of the considerable change in their life situation. The deceased partner is likely to have previously managed all the finances, household structure and rates administration.

Applicants can be confused when trying to apply on their own, but don’t want to take up others time and be a burden. While they are trying to do their best, they struggle to know where to start. There are genuine attempts to comprehend what is needed but they get confused in the process, and need to be supported through the process. Often they will need to learn to drive and will need to gain the confidence to travel independently.

“She is a recently widowed lady whose husband used to deal with the rebates and such like. She is not a well woman and rarely leaves the house. She gets quite overwhelmed if she has to deal with bureaucracy so we visit to make it easier for her.” COUNCIL STAFF MEMBER

“She came into the offices for her rebate appointment. Her husband had just passed away and she needed the rebate to continue to live in the property. She cried throughout the appointment and was very embarrassed. Her husband did all the finances and she was now having to learn to cope with everything and to pay for everything herself.” COUNCIL STAFF MEMBER

“She’s never filled out the application form. Her husband’s always done it” COUNCIL INTERPRETER

Key insight #11

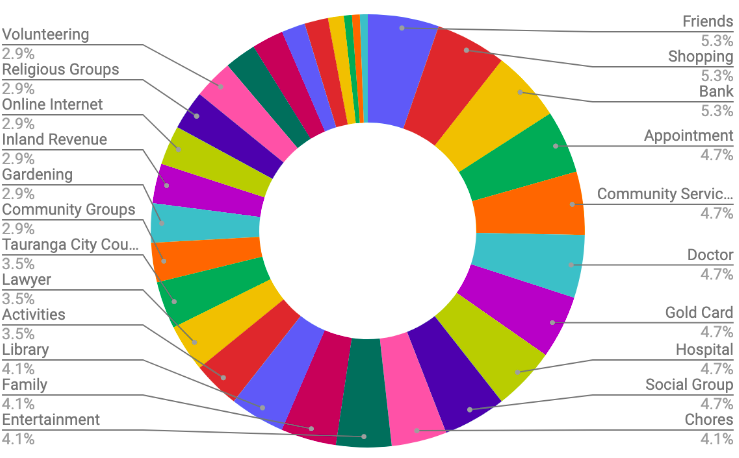

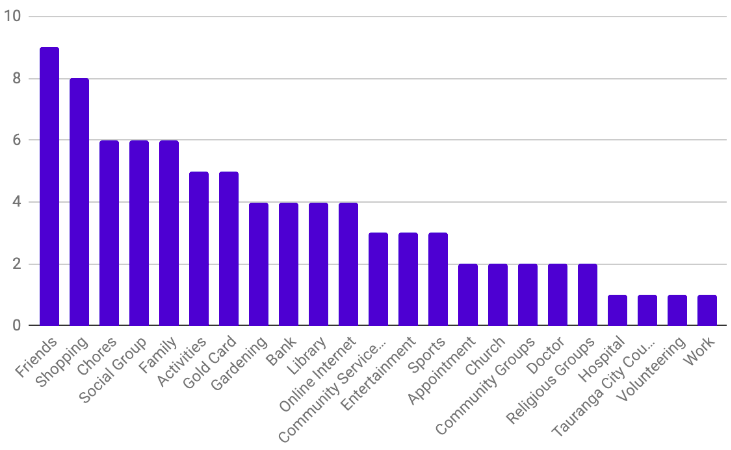

Leverage the best channels for awareness and support.

One of the biggest barriers to applying is that ratepayers don’t know about Rates Rebates and that they may be eligible. Various channels used by this audience can be leveraged to raise awareness and support the application process.

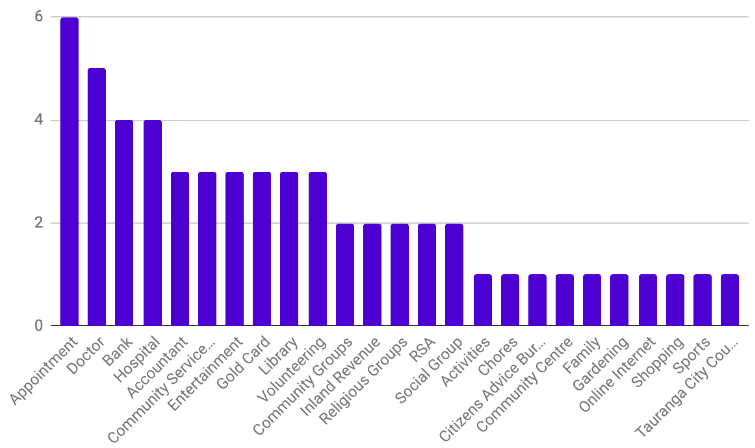

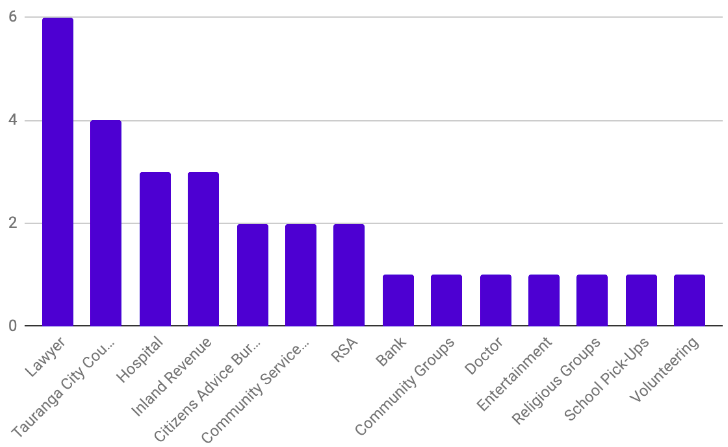

The research identified common groups, organisations and entities that could be used to support information, communication and other assistance for these customers.

Spending time with friends and family rated highly, and we also learned that social groups are already are the most common way that people hear about Rates Rebate. Council and Libraries were also identified as effective channels for reaching the target audience.

There is also an opportunity to raise awareness through commonly used Gold Card and Community Services Card channels, and during interactions with health professionals and doctors, in local practices and hospitals.

Supermarket shopping is a common and frequent activity and may offer additional reach through supplementary advertising. IRD interaction is less frequent, but common across all ratepayers so could offer reminders or additional information.

A good proportion of this audience can be reached online through various approaches, especially leveraging social media.

“Certainly everyone had heard about it here, and I think it was like a little bushfire that went through” RETIREMENT VILLAGE RESIDENT

“I’ve got to go to the doctor on Friday. Last year I was often at the hospital” PRIVATE HOME RESIDENT

“Skype and Facepage. Because we talk to Adelaide quite often, and England of course” RETIREMENT VILLAGE RESIDENT

Further information and frequency of interactions are available in the Appendix.

Appendix #1

Automation feedback

The following questions about automation were asked via two online surveys, and during the face to face interviews with applicants.

Permission to prefill the application form

“And they all moaned because they thought they should just get it and not have to fill it out every year”

“Reams of stuff to fill in”

Permission to share information from other government agencies

“You should know what it is”

“The rates office knows all the answers really. They know what we pay and they know what the village pays, so why don’t they just fill it in and I’ll just sign it”

Permission to share information from other government agencies

There was less interest in sharing information from government agencies, than having the form automatically prefilled based on the previous years application. Some of the reasons why applicants chose ‘No’ to this option were:

- Previous system errors with agencies had impacted their eligibility for other entitlements

- Didn’t understand how Ministry Social Development were relevant to them

- Couldn’t understand how this could be automated

- Didn’t think Inland Revenue was relevant because they didn’t earn any income

- Had an accountant so didn’t need input from Inland Revenue

Appendix #2

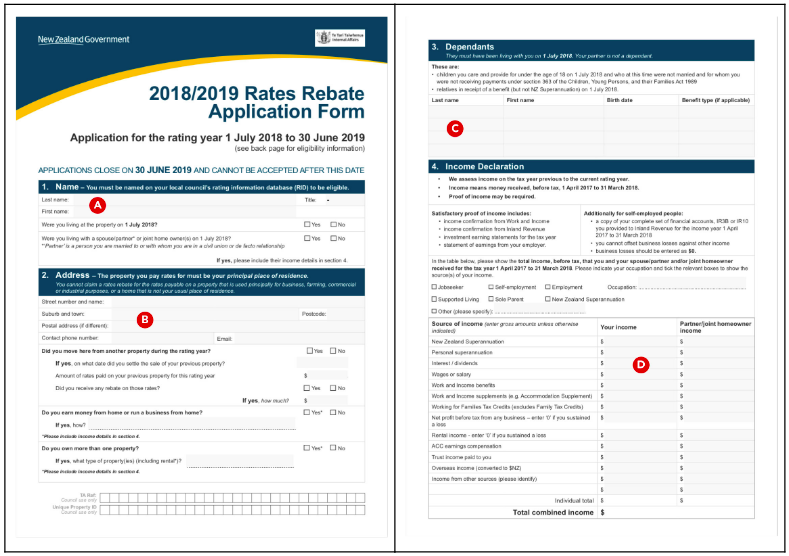

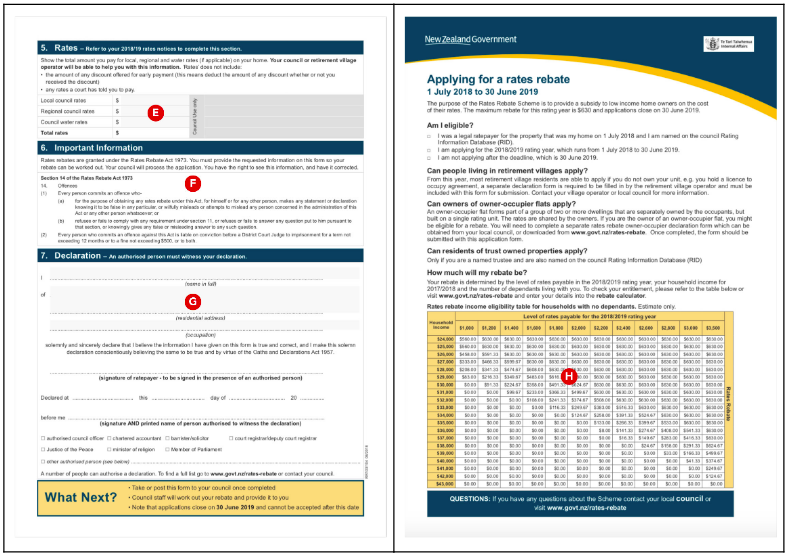

Completing the paper application form

As part of the interview process we observed the nine applicants filling in the 2018/2019 Rates Rebate paper application form. We asked them to talk about what they found challenging as they were going through the process. Overall, applicants found the size of the text too small and difficult to read. A lot of information and instruction was skim read but not absorbed.

Name (A)

- First name / Last name fields were often transposed. People automatically wrote their first name in the Last Name field.

- Title was often overlooked

- Some were unsure as to which name to use, as they were known by their middle name, or a variation of their name. These names would be different to what the ‘official’ name stated on the Rating Information Database (RID).

Address (B)

- People would start to write their whole address in the first field, then get confused at what they should write in Suburb/Town and postal.

- A lot of people knew their postcode

- A lot of people had an email address

- People were often confused when filling out the question ‘Did you move here from another property during the rating year? If they selected ‘No’, they didn’t realise they could skip the next question ‘If yes, on what date did you settle the sale of your previous property for this rating year?’. They would try and fill out the next questions and get very confused. It would take them a while to figure out that they could have skipped those questions.

- Retirement village residents sometimes have their own individual street address (number and street name) within the retirement village, but most assumed they could just use the format they would use as a postal address

Dependants (C)

- This question wasn’t relevant for the group we interviewed. They either wrote N/A or put a line through the boxes. However, this information is not legally required by the Act, and its possible that this question may add a barrier to completion.

Income Declaration (D)

- People skim read the instructions, filled in the tick box (New Zealand Superannuation) and then wrote ‘Retired’ in the Occupation field. This is a duplicate of information as there is a NZ Superannuation $ field below, and an addition ‘Occupation’ question on the Stat Dec page. Ideally the repetition could be removed.

- The format of the ‘Source of income’ fields worked well and there were no issues with understanding where to put the $ amounts.

- The problem with the income information was that a lot of the applicants didn’t understand that the requirement is for Gross income rather than Net income. People would either guess the amount, or look at their bank account to see what comes in every week/fortnight and do some complex maths to estimate what that would be over a year.

- There was confusion over the difference between NZ Superannuation and Personal Superannuation.

Rates (E)

- Most people guessed their rates or left the field blank for the council to fill in.

- People were uncertain of the different types of rates (local, regional, water)

Important Information (F)

- This was skim read by the applicants

Declaration (G)

- Name, Address and Occupation fields are all double up from previous parts of the form. Is there a way to structure this so this data is only written once?

- ‘Declared at’ caused confusion for a lot of people, as they started to write the date in this field. When they realised their mistake they weren’t sure what the term meant. Most eventually guessed it as ‘place’, but didn’t realise that this was for the authorised witness to fill in.

Calculation table (H)

- This table was often overlooked, but when prompted the applicants found it easy to interpret. Retirement village residents don’t have access to their rates amounts, so are unable to use this table.

Appendix #3

Frequently used channels

One of the biggest barriers to applying is that ratepayers don’t know about Rates Rebates and that they may be eligible. As part of our research we asked questions to inform how we might better raise awareness.

Some of the research surfaced common groups, organisations and entities that could be used to support information, communication and other assistance for these customers.

What keeps you busy

These channels have been grouped into three sections; ‘Often’, ‘Sometimes’ and ‘Rarely’ to describe the general frequency of interaction with these groups.